Faces of 2025: who shaped higher education headlines this year

Jane Harrington

After months of discussion about whether university mergers would save the UK’s ailing higher education sector or simply add to its woes, the universities of Greenwich and Kent boldly put themselves forward as guinea pigs, announcing in September that they would be joining forces to create a new “superuniversity”. Both Jane Harrington, Greenwich’s vice-chancellor, and Randsley de Moura, Kent’s acting vice-chancellor, were quick to dismiss the idea that the decision was a financial one – but the denial has met with some scepticism given the £6.3 million underlying deficit Kent reported in 2023-24. Nonetheless, as even the government appears to view mergers and consolidation as one of the only ways out of the financial crisis gripping institutions, other university leaders are sure to be keenly watching the progress of this one – and whether the sector really can embrace collaboration over competition.

Helen Packer

Source:

University of Greenwich

Paul Wiltshire

Under Tony Blair’s premiership, the idea that going to university would ultimately lead to higher wages was well established. Today, figures show that graduates on average earn £42,000 – compared with just £30,500 for school-leavers, which is the largest wage gap on record. But the “graduate premium” itself has been labelled a “myth” in some quarters – and that is partly as the result of the efforts of one man. Paul Wiltshire, a semi-retired accountant and father of four UK university graduates and current students, has repeatedly banged the drum that figures used to justify university attendance overestimate the monetary value of a degree by failing to account for prior academic attainment. He has had some success, with the statistics watchdog admitting the overall average could be misleading. The news has been eagerly embraced by many of the sector’s critics in the press and coincided with another Labour prime minister deciding that the pivotal 50 per cent participation target was “not right for our times”.

Patrick Jack

Source:

John Lawrence/Telegraph Media Group Holdings Limited 2025

Laura Murphy

It’s no secret that Chinese students and the millions of pounds they pay in tuition fees have been propping up UK academic research for years. But at what cost? This year the troubling influence of China on British academia was highlighted by Beijing’s efforts to shut down a research project by human rights professor Laura Murphy into forced labour practices endured by Uyghur Muslims. Faced with legal threats, intimidation of student recruitment staff and internet restrictions, her employer Sheffield Hallam University blocked publication of Murphy’s project. Although her research unit was shut down, the university eventually conceded it had infringed Murphy’s academic freedom and apologised in November. With many UK universities still massively financially dependent on the 154,000 Chinese students filling campuses, many fear that more subtle forms of political pressures on institutions will make it harder for researchers to take the same critical line as Murphy.

Jack Grove

Source:

Christopher Thomond/Guardian/eyevine

Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee

It started with Stanley, Shore and Snyder. Three professors from Yale University who left Trump’s America just as the White House’s hostilities towards higher education were beginning. They all went to a grateful Toronto but since then the floodgates have opened worldwide. As Trump’s attacks have escalated, countries around the globe have benefited from a previously unthinkable weakening of US research strength. Almost 300 researchers applied for “scientific asylum” at Aix-Marseille University in France, anti-fascist scholar Mark Bray fled for Spain amid death threats, and the UK has attracted a handful of top scientists through a new Global Talent Fund. But Switzerland nabbed potentially the biggest coup. Married Nobel prizewinning economists Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee have announced they are leaving full-time posts at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to take up endowed professorship positions at the University of Zurich. Many of those who have left have not spoken publicly or cited “personal reasons” – but their actions speak loudly enough.

Patrick Jack

Source:

Associated Press/Alamy

Dharmendra Pradhan

Changes made earlier in the decade paved the way for India to open up to international universities but 2025 was truly the year when the Indian branch campus phenomenon took off. Education minister Dharmendra Pradhan has become the public face of a policy shift that looks set to have profound effects on higher education across the world. In April, he confirmed that “around 15 foreign universities” were expected to set up campuses in India in the 2024-25 academic year. Visits from UK and Australian dignitaries brought more announcements and, in September, the University of Southampton won the race to become the first to start teaching courses. Concerns already abound that India is becoming saturated with foreign universities, prompting some to look for the next location that offers similar potential. But India’s vast size and desire for higher education mean many believe there is still untapped need in the country. As governments in the traditional “big four” destinations continue to crack down on onshore enrolments, transnational education looks set to become ever more important in the years ahead.

Tash Mosheim

Source:

Pradeep Gaur/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

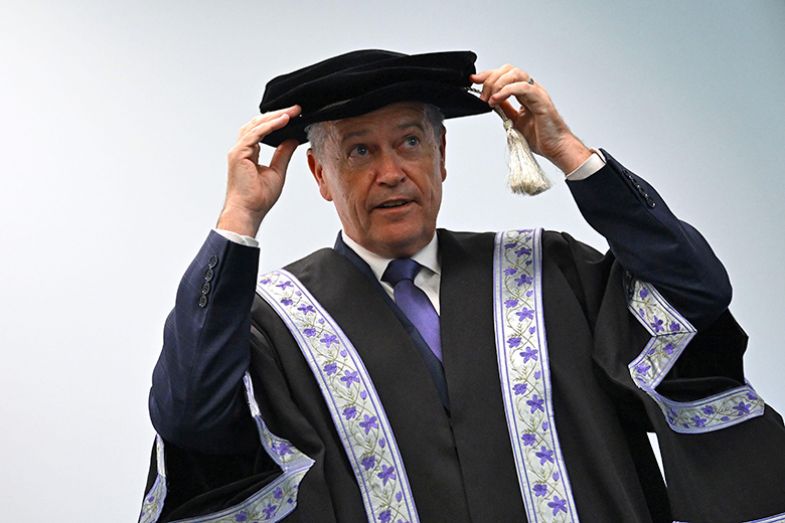

Ian Chapman

It didn’t take long for Ian Chapman to set out his vision for UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), Britain’s £9-billion-a-year research funding agency. Days after becoming its chief executive, Chapman told vice-chancellors at Universities UK’s annual conference in September that their institutions might need to start doing “fewer things but doing them really well” and criticised what he called a “crumbs for all” approach to funding. Further detail of what this might mean for universities was revealed in the government’s post-16 skills White Paper in October, which outlined plans for “more focused volume of research, delivered with higher-quality, better cost recovery” and a desire for more “teaching-only” specialists. How this research concentration will play out has yet to be revealed but with Chapman and science minister Patrick Vallance aligned on the big picture, particularly when it comes to investing more in government-aligned research, major changes are likely to unfold in 2026.

Jack Grove

Source:

Giuseppe Lami/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

Mosa Moshabela

It has been a fraught year for South African higher education, with violent protests and arson attacks occurring at Fort Hare University and the University of the Free State. Africa’s highest-ranked university, the University of Cape Town, has also been no stranger to disruption, with 80 students occupying buildings during disputes over tuition fee debts and accommodation grievances. Mosa Moshabela, the university’s vice-chancellor since August 2024, has been thrown in at the deep end but has overseen the rise up the rankings of the only African institution in the world top 200, despite the issues. Even though South African universities have lost all US funding due to Donald Trump’s cuts to USAID, Moshabela has doubled down on UCT’s relationships with American universities, telling Times Higher Education: “As university leaders, we have to insist that the world can be at war, but science is not at war.”

Juliette Rowsell

Source:

Brenton Geach/Gallo Images via Getty Images

Bill Shorten

No Australian vice-chancellor has hit the ground running quite like former federal opposition leader Bill Shorten. The erstwhile unionist and politician, Australia’s next prime minister until he unexpectedly lost the 2019 election, has embraced a third career in higher education with humour, gusto, principle and realpolitik. He guided the University of Canberra out of financial crisis while using his platform at one of the sector’s smallest players to deliver big-picture truths about the academy’s wilting social licence. Shorten railed against underpayment of staff, overpayment of executives and harassment on campus, saying the best defence from outrage was to avoid causing it in the first place. He took concrete steps to attract blue-collar students, promised a retirement home on an unused university paddock and proposed an adaptation of the 1990s Training Guarantee to help safeguard Australia’s sovereign skills. Colleagues might not always like Shorten’s message but they would be ill advised to ignore it.

John Ross

Source:

Australian Associated Press/Alamy

Rumeysa Ozturk

It was a difficult year to be an international student in the United States. With president Donald Trump’s government revoking visas left, right and centre, the message was clear: toe the line or risk deportation. Turkish PhD student Rumeysa Ozturk was one of those who discovered at first hand the perils of displeasing the administration. After penning an article critical of Israel and the war in Gaza in her campus newspaper, the Tufts University student’s visa was revoked in March and she was arrested and held in a detention centre. The move sparked outrage and provoked protests from fellow students until Ozturk was eventually released in May. She was finally allowed to resume her research in December. Although the judge hearing her case condemned the chilling of free speech among non-citizens, the US administration doubled down on its promise to expel foreigners it viewed as antisemitic. As a Department of Home Security spokesperson said after the judge’s ruling: “Visas provided to foreign students to live and study in the United States are a privilege not a right.”

Helen Packer

Source:

Joseph Prezioso/AFP via Getty Images

Liang Wenfeng

ChatGPT has dominated the AI world since it hit the mainstream in 2022 but Liang Wenfeng, co-founder and chief executive of DeepSeek, has built a model to rival the American giant, showing the potential of Chinese science. DeepSeek’s R1 release sent shockwaves through the global tech sector earlier this year – offering a large language model with the performance levels of ChatGPT with reportedly far lower training costs. Liang, a Zhejiang University graduate, leads a young team including graduates and current students from leading Chinese universities, among them Tsinghua and Peking. He has said that the group spans recent graduates of top universities to late-stage PhD candidates, a mix that has drawn attention to China’s expanding AI talent pipeline. China has already begun to dominate the world of AI research, with countries keen to collaborate in fear of being left behind. Given the US’ research upheaval, the Eastern giant looks primed to take over as a global science leader, potentially leading to many more talented graduates like Wenfeng staying at home to build the companies of the future.

Tash Mosheim

Source:

Getty Images/Alamy montage